A 1975 study by Gilles and Powesland found that ‘speech is more powerful than the written word or a visual image in making a good impression’ so we better do it well. Since all communication of your assistant is related to the persona (the words it uses, the way it reacts to things, etc.) we strongly encourage you to create a well defined persona before writing the prompts (things the assistant says). Otherwise, the entire flow needs to be reconsidered afterwards and all prompts need to be rewritten. This can be a tremendous amount of work.

What is a persona?

According to Adva Levin, head of Pretzel labs, a persona is part of someone’s character, as perceived by others.

In their book Voice Interface Design, Cohen, Giangola and Balogh define persona as follows:

‘Persona” is defined as the role that we assume to display our conscious intentions to ourselves or other people. In the world of voice user interfaces, the term “persona” is used as a rough equivalent of “character,” as in a character in a book or film. A more satisfying technical definition of “persona” is the standardized mental image of a personality or character that users infer from the application’s voice and language choices. For the purposes of the VUI industry, persona is a vehicle by which companies can brand a service or project a particular corporate image via speech.’

Why is this important?

Some people say that we shouldn’t spend (much) time on defining a bot persona. They claim that the way the bot functions and what it can do is way more important than how it comes across. However, when we look at it from a user experience or a commercial point of view, it is a wise decision to spend time on a persona. After all, we’re talking about the voice, and with that, the image of your brand. You do want some control over that, right?

A very important thing to keep in mind is that your users will automatically assign a personality to your assistant. Based on what they know about your brand combined with the sound of the voice, the vocabulary it uses, the prosody (rhythm, intonation) and so on, they create a mental image of ‘who’ they’re dealing with.

According to Cohen, Giangola and Balogh, “There is no such thing as a voice user interface with no personality.” This basically means that if you don’t design your assistant’s persona yourself, your customers will do it for you. Read on to learn how to create a persona you think best suits your brand.

How far should you take the personality design?

This depends on the purpose of your assistant. If you’re designing one for, for instance a theme park or some other business in the entertainment industry, you can go pretty far when it comes to characters. You can focus on jokes, quotes, extended small talk, etc. However, if you’re designing a personality for a bank or insurance company you may spend just as much time on crafting the character, but it has to be far more serious. People perceive their financial business as something serious, so better not to joke about it. In our last article we pointed out that it is essential to always keep the end user in mind. This is a perfect example of the importance of doing so.

Gender

You’re likely to have heard something about gender bias in voice assistant technologies. In September 2019, Unesco issued a report arguing that voice assistants like Google’s perpetuate “harmful gender bias”: “I’d blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education”. According to the report we are amplifying gender bias by using female voices for assistants in “servile, obedient and unfailingly polite,” roles.

The option to let you user choose between male and female voices, or even a genderless one like Q, may sound like a perfect solution. However, we might be running into some difficulties here. According to the late Clifford Nass, professor at Stanford University, women talk in a different way than men. Women use more personal pronouns (I, you, she) while men use more quantifiers (one, two, more). Nass: “If someone listening to a voice interface hears a male using feminine phrasing, they are likely to be distracted and distrustful. Companies preparing scripts for computer voices will have to take factors like this into account.”

He also found that people tend to perceive female voices as helping us solve our problems by ourselves, while they view male voices as authority figures who tell us the answers to our problems. We want our technology to help us, but we want to be the bosses of it, so we are more likely to opt for a female interface. Also, women have said an authoritative male voice talking to them about their finances irks them enough to avoid using that bank entirely. Therefore, it is essential to involve your end users early on in the process to see what they think of the voice. We’ll come back to that later.

Canvas

A useful tool when creating a persona is a persona canvas. A canvas includes the most important aspects you must consider when creating a persona (search for ‘conversation design canvas’ on Google to find the one that suits you best. Robocopy offers a quite extensive one as part of their Conversation Design course).

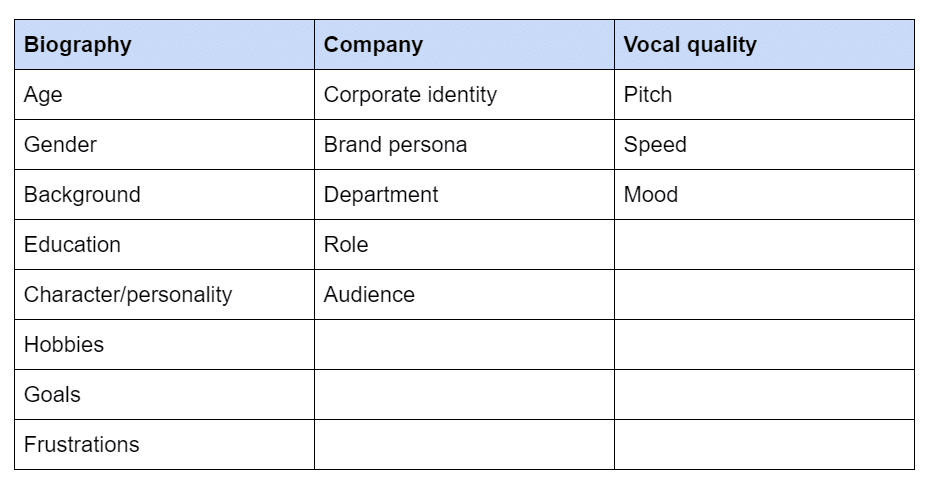

The persona can be roughly divided into three parts:

Most importantly: create a consistent user experience. In order to do so, we recommend that you also make lists of words and phrases the assistant uses and a list of ones it definitely never uses. This is especially useful when your project involves different conversational writers.

Tip: designers often take an actual person in mind, someone they want their assistant to resemble. This makes it easier to create a consistent, real-life character.

Role

You should also consider the role the assistant has in your users’ lives. If you choose to use a friend role it’s essential to use very different words and phrases than if you’re creating a financial advisor persona in an authoritative role.

End users

According to Cohen, Giangola and Balogh ‘A successful, appropriate persona strikes the user as familiar, both linguistically and socially. Persona design must therefore consider who these users will be and in what contexts they will use the application.’ To develop a compelling persona, consider the demographics, attitudes, and lifestyle of the target audience.

Avatar

Although for voice first experiences an avatar may not be necessary, it can help you in bringing your assistant to life and thus be more consistent. An avatar can be in many forms, some of which are:

- a cartoon

- an image (not suitable for chatbots since based on the image the audience may think the bot is a real person and you would want to avoid this)

- a sketch of a robot

- an abstract form like Google assistant

(There’s a lot more to consider about the use of avatars in conversational interfaces, but we’ll leave that for another article).

User testing

As mentioned in our last article, it’s important to involve your users as soon as possible in the process. How do they perceive the voice? Are the speed, pitch and warmth ok? What is their opinion on, or feeling about, the fact that it’s a male or a female voice? Does the vocabulary match with their expectations? What is their overall feeling about the persona? And, in case of using an avatar, how is that perceived?

Some more things to keep in mind

Make sure that the tone of voice and the way the bot answers are consistent

Empathy is an essential trait of a voice assistant. Again, this can differ per type of organization, but no empathy is never a good idea. Therefore, make sure to hire good copywriters and don’t leave it to the binaire IT developers (they have a lot of work in making the assistant function anyway 😉 ).

Reactions on rudeness: how does your assistant react when it’s being cursed at?

Future

So, where are we heading regarding personas?

We already know that people react differently to various voices and personas. When we take this a step further, there’s the fact that we human beings tend to relate more to people who are a bit like ourselves. Chances are that a woman is more willing to accept something from another woman, or that an introvert is more willing to take things from another introvert.

In order to get as much as possible out of this we need to know our users; who are they and what are their personalities like? And this is where we enter the very interesting field of ethics again: how far are we allowed to go and, just as important, how far are we willing to go? Where does a good user experience end and manipulation start? And what will it do to our brand voices? Will they still exist or will every brand have multiple voices, aimed at different target audiences?

And what about mood determination? Based on the user’s tone of voice the assistant changes it’s choice of words, speed of speech, tone of voice. This can be either to help the user relax or to make him more upbeat. This is where we enter the field of persuasive design. Are we willing to implement this? And then again, how far are we willing to take this? And until what point is the user willing to accept this?

One thing is for sure: there are interesting times ahead.

On May 14th, we organize a Digital Talk about how to create the best user experience for voice apps, with great cases from companies like bol.com. Feel free to join us (the event is in Dutch)!

Sources

Books

- Designing Voice User Interfaces by Cathy Pearl

- Voice Interface Design – book by Michael H. Cohen, James P. Giangola, Jennifer Balogh. Voice User Interface Design @Team DDU’. Apple Books

- Wired for speech by Clifford Nass and Scott Brave

Web

- Unesco report “I’d blush if I could”

- Dribble.com: Designing for voice – 4 principles in voice first technology

- Part 1 of this series: Designing voice user interfaces – the basics

Photo by Med Badr Chemmaoui on Unsplash

Ook interessant

Podcast Shaping the Future: “Zonder experimenteren vaar je blind”

Eén datafundament is niet genoeg voor AI